Love drives.

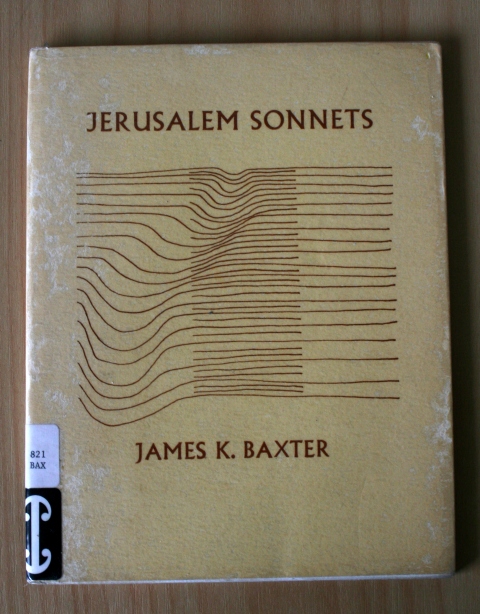

Towards the end of last year I went hunting for some replacement Allen Curnow in the NZ poetry shelves of Arty Bees. An acquaintance who’d borrowed the beautiful, second-hand Curnow I’d found there had cheerfully denied any knowledge of it when we met on the corner of Wakefield and Tory, so I hoped to chance on more of his poetry. Curnow was absent that day, but this turned up instead.

It seems likely, given the ‘NZ Room’ sticker on the spine, and the barcode inside the cover, that this copy of Jerusalem Sonnets by James K. Baxter was purchased by Arty Bees from one of Wellington City Libraries’ regular book sales. Probably no-one had taken it out in a while: ‘STACK’ is written in red biro on the library’s shelving sticker.

Maybe it was a City librarian who affixed the sticky plastic to the brown and straw-gold loose cover, catching a few air bubbles. (The cover is a brighter, less muddy gold than in the photo.)

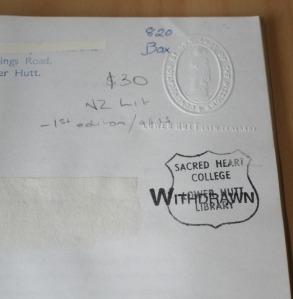

Before the City library owned it, it belonged to the Lower Hutt Library of Sacred Heart College. The collection seems so little handled – the pages barely marked, foxed or dog-eared – that I wonder if it was hidden permanently under the librarian’s desk, Baxter’s references to sex and pot and crabs deemed too explicit for impressionable minds. I should probably store it somewhere darker than in the leaning row under the windowsill on my desk, but I like to have it close at hand.

I imagine a conscientious and literature-loving Sacred Heart librarian who, having heard that Baxter wrote the sonnets while living at Hiruharama / Jerusalem, the settlement on the Whanganui River where Suzanne Aubert founded the Sisters of Compassion, decided that this Catholic son’s work must be included in the school’s collection. She must have been onto it, to get one of the first 500 copies. But after all, one of Sacred Heart’s six houses is named for Aubert. On receiving the collection, our librarian reads it (with some pleasure, we hope), and then slips it straight into a drawer, so as not to raise controversy amongst parents and disquieting giggles between the girls. I hope she pulls it out from time to time to revisit the poems.

I’ve never had the inclination to be a first-edition fiend. I just don’t see the point of collecting them for their own sake. (This past weekend at a neighbour’s garage sale, I recognised the local man who, two years ago, responded to my Freecycle ad and picked up my mother’s brittle and browned Coronation newspapers. Having failed to provoke interest either on Trade Me or at Arty Bees, the papers were headed for the recycling bin. I was glad they still had a life in someone’s mind.)

Nonetheless, the fact that this is the first edition of Baxter’s Jerusalem Sonnets is part of why I love it. I love its air of contingency: here is an object produced with care and attention, but likely to perish within a few years unless protected in library stacks or a bibliophile’s careful shelves. It’s made of A4 paper and light card, fastened with staples. It’s a zine-like production. It feels both personal, and professional.

By contrast, my great-aunt’s self-published volume of ‘verse’, in which swaying multitudes of flowers sigh, wander, cluster, gaze and glimmer, sports a durable blue cloth-and-board cover with a textured, watery effect. I never met her. She was told she had a nervous disposition, and died before I was born.

The Jerusalem Sonnets paper is of a sufficient, serious weight. (Colin Durning, to whom the poems are addressed, paid for their first imprint at the University of Otago Bibliography Room.) The poems are typo-free, impeccably type-set, and well-placed on the page. The sinuous line drawing on the cover, reminiscent of a topographical map’s channel or ridge, is by Ralph Hotere. Since 2001 the drawing has found a preserved, if miniaturised, life on the cover of the annual online collection Best New Zealand Poems. (You can also see the drawing here, but as in my photo above, the whole image seems horizontally squashed. What is it with photos on the web?)

I also love the evidence of past ownership, particularly the school’s marks: the embossed stamp in the top right-hand corner inside the cover, in which the words ‘Congregation of Our Lady of the Missions’ surround a robed, haloed figure. Some librarian’s old-fashioned handwriting, looking like a great-aunt’s: ‘820 Bax’. The whited out top line of the address: ‘Convent of Our Lady of the Mission’, and the school’s badge-stamp. And I love reading the poems. I like their colloquial, personal and narrative qualities, their energy and movement and specificity, and the questions they ask.

I also love the evidence of past ownership, particularly the school’s marks: the embossed stamp in the top right-hand corner inside the cover, in which the words ‘Congregation of Our Lady of the Missions’ surround a robed, haloed figure. Some librarian’s old-fashioned handwriting, looking like a great-aunt’s: ‘820 Bax’. The whited out top line of the address: ‘Convent of Our Lady of the Mission’, and the school’s badge-stamp. And I love reading the poems. I like their colloquial, personal and narrative qualities, their energy and movement and specificity, and the questions they ask.

Many months ago I wrote a guest post on poet Helen Heath’s blog about how much I enjoy my Kindle. There wasn’t room in that post to discuss a Kindle’s drawbacks. One of the most obvious is that on a Kindle, you can’t flick through the pages. It’s laborious to find the passage that you’re thinking of. As others have observed, when you read a paper book, often you haven’t marked that passage: you simply know that it’s somewhere towards the bottom of a left-hand page, and, oh, it comes after this bit, but before that bit (and meanwhile you’re finding other sections you liked, and which are relevant to your line of thinking).

On a Kindle, the equivalent of ‘flicking’ is unrewarding and dull, involving much back-and-forth on screens which lack any of the interest of the text’s actual pages. When reading a non-chronological, unconventional novel like Jenny Erpenbeck’s Visitation, the difficulty with flicking became a downright problem, preventing me (not the most retentive of readers) from figuring out who was who. If I had been more committed to the book, I would have made notes: on paper, of course.

But conversely, I think that if I’d read Visitation in a more easily manipulated three-dimensional form, my commitment to it would have been greater. I imagine that reading Egan’s wonderful Visit from the Goon Squad on a Kindle might have been similarly frustrating, but thankfully I bought a proper copy of that. And while I need to keep every book I read, I do want paper copies of the books I adore. (On my list for regular searches at Arty Bees is Virginia Woolf’s The Waves.)

It wasn’t long after my post on Helen’s blog that I found this Baxter. Contemplating my love for it, I began to imagine a future in which paper books are the exception. I do believe that small runs like this 1970 edition of the Jerusalem Sonnets (500 copies) will survive, for the same reasons that the zine scene is flourishing. However, in a world in which a poet can tweet and Facebook her way to thousands of readers, maybe it’ll be a brave writer who publishes only on paper. I find it moving to look at these pages knowing that this edition marks the first time that a mass of New Zealand readers encountered these sonnets.

I also imagined a future in which hard-copy books might only be produced as souvenir editions, or because they will ‘find a market’ among nostalgic fetishists who resist the onward march of technology. The prospect saddened me. One reason this book means something is that you know, looking at the typeset poems on the pages, that the circle of passionate response to Baxter’s poems had yet to spread far. (Not that it took long: as the site The Black Art – very much worth a visit – tells us, 2000 more copies were published within 18 months of this edition.) People cared about this publication and made it happen not because of market forces, but for reasons to do with life force, and love, and art, and concentrated effort.

The title of this post is taken from Poem for Colin (6) from the Jerusalem Sonnets:

The moon is a glittering disc above the poplars

And one cloud travelling low downMoves above the house – but the empty house beyond,

Above me, over the hill’s edge,Knotted in bramble is what I fear,

Te whare kehua – love drives, yet I draw backFrom going step by step in solitude

To the middle of the Maori nightWhere dreams gather – those hard steps taken one by one

Lead out of all protection, and even a crucifixHeld in the palm of the hand will not fend off

Precisely that hour when the moon is a spiritAnd the wounds of the soul open – to be is to die

The death of others, having loosened the safe coat of becoming.James K. Baxter

Swimming with Books went visiting…

over at the blog of my lovely publisher, Victoria University Press. It’s about the writing process. And things.

It starts like this:

Can a writer alter the type of story she instinctively writes, or the temporal and psychological structure of that story, and produce a new story that is not false, unsuccessfully experimental or try-hard, but has conviction and internal strength?

Here’s a story I often find myself writing. In the story’s present my protagonist is strongly affected by an event or series of events that’s already complete, and usually of some duration and complexity. The effect of the inciting event on my protagonist is inevitably emotional and psychological. Therefore, in order for the reader to properly understand the protagonist’s current state of mind, the event needs to be narrated in detail.

More (scroll down a bit)

Where do ideas come from?

Elizabeth Gilbert (Eat Pray Love) is of the opinion

that ideas and creativity circle the world like gulfstreams, looking for ‘portals’, and if you’re not open to them, they’ll go and find someone who is. I get the impression that she means actual gulfstreams of ideas, just as she seems to mean actual angels when she talks about angels.

I too entertain some unverifiable ideas, though I don’t have Gilbert’s ability to believe in discrete, human-like supernatural entities. But for writing purposes, I’ve found that pretending to believe can be useful. Our imaginations believe and act on what we tell them.

Back when I was writing the first draft of Acts of Love, I tussled with the character who eventually turned out to be Stella. At that point she had a different name, and having written a few chapters, I couldn’t figure out anything further about her or what she might do. Stuck stuck stuck. One day I got myself into a bit of a makebelieve trance and told her I’d ‘interview’ her. My agreement with myself was that she temporarily existed outside the world of the book. She was to talk to me, the writer, about the way I was writing her, and about what might happen to her in the novel. Then I wrote non-stop in my notebook in ‘her’ voice for about forty-five minutes. Amongst a load of twaddle, she said something which changed the direction of her character: ‘I’m not as angry as you’re making me out to be.’

That was a surprise. At the time I couldn’t see any way for her not to be fundamentally furious. But over the following months she changed shape (and name) into a less whiny, more active person. I’m not suggesting that I actually communed with her ‘spirit’. I knew, at the time, that I was fooling myself. And I understood that something in me knew more about her character than I consciously knew at the time.

In the same Radiolab podcast that I linked to above, Gilbert also talks about finding the title for her bestseller Eat Pray Love. Essentially, this consisted of gently asking the manuscript to reveal its name to her.

I thought this sounded a little kooky (though really I wish I had Gilbert’s ability to believe like this – it’s as though she never became divorced from that childlike part of herself), but historically I’ve been bad with titles. I still haven’t officially graduated my MA – ten years this year – because I’ve been too embarrassed by my collection’s title to lodge it in the university library. I really must get onto that.

Recently I needed to find the title for a story and having just listened to the podcast, thought I’d trick my imagination into setting up a quick link into my conscious mind. There’s a fairly left-field body-mind thing that I do, so I did that, and asked the story for its title, and ta-da, there it was. Not perfect, not particularly memorable (‘Everything That Rises Must Converge’) but good enough for a deadline and a lot better than any of my previous attempts.

This idea that so much of what we write comes out of the non-cognitive parts of our minds does fascinate me. In the Guardian Weekly (11.02.11), John Gray wrote in the The Hunt for Immortality that H. G. Wells, having absorbed Darwinism, was convinced that humanity would become extinct unless right-thinking people seized control of evolution. He thought the Bolsheviks would do a great job of creating a higher species, and found Lenin ‘very refreshing’. He wrote that if the Soviet state killed lots of people, ‘it did on the whole kill for a reason and for an end’. Chilling.

However, Gray points out,

“His scientific romances tell a very different story. When the time traveller journeys into the future, in The Time Machine, he finds a world built on cannibalism, with the delicate Eloi seemingly content to be farmed as food for the brutish morlocks, and travelling on into the far future finds a darkening Earth where the only life is green slime. In The Island of Dr Moreau the visionary vivisectionist performs vile experiments on animals with the aim of remaking them as humans. The result is the ugly, tormeted “best-folk” – a travesty of humanity.

Wells’s fables were a kind of automatic writing – messages from his subliminal self that his conscious mind dismissed. They teach a lesson starkly at odds with the one he spent his life preaching: the advance of knowledge cannot deliver humans from themselves, and if they use science to direct the course of evolution the result will be monsters. This was Wells’s true vision, always inwardly denied, and for much of his life expressed only in his scientific romances.”

Gray suggests that despite what Wells thought he believed about the construction of a ‘higher species’, Wells’s subconscious knew better: that it was wiser, closer to the truth, and more far-seeing. (Though ‘closer to the truth’ just shows my own biases.)

How can we know ourselves well enough so that, maybe, we can write the strongest stuff in us without it having to trickle down through the convoluted pathways and firewalls we may have set up between our dreamworld and our conscious minds? The best way I’ve found, so far, is just to write, and write some more. More on that another time.

Franzen: Correction

Back in February, I commented that I had felt ‘consumed by’ Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom and enjoyed the experience less than reading Patrick Evan’s excellent Gifted (a pointless comparison). I used the phrase ‘Franzen’s obvious manipulation of his readers’.

Back in February, I commented that I had felt ‘consumed by’ Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom and enjoyed the experience less than reading Patrick Evan’s excellent Gifted (a pointless comparison). I used the phrase ‘Franzen’s obvious manipulation of his readers’.

Who was I kidding? I love obsessing about characters, lying awake imagining myself living their lives, replaying scenes in my head, and I don’t at all mind being manipulated by a master storyteller.

I love the enormous scope of The Corrections and of Freedom. I love the richness of Franzen’s characters. I admire his facility with structure. I love his sentences.

One of my reading friends thinks several of Freedom‘s characters are caricatures. I can’t comment because my critical faculties were switched off while I read. It doesn’t take much to flick that switch: a good enough story, an authoritative hand, compelling characters.

If I had been honest with myself back in February, I would have said that I regretted reading Freedom so fast; that I wish, when reading novels that make me voraciously curious about their characters, I didn’t fly over the paragraphs in a hectic race to find out what happens. I felt grumpy while reading Freedom: couldn’t focus on anything practical, neglecting domestic duties and writing. The grumpiness had to do with feeling out of control, and being reminded of an earlier period of my life when I only read to escape. Also, I hadn’t given myself permission to rush. In my reading plan, Freedom wasn’t a holiday distraction. I wanted to learn from it. But at the time, my desire to relieve the tension of not knowing what happened to the characters was greater.

Right now my husband is reading the final chapters of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows to our son, and on wandering downstairs to make a cup of tea, I hear details that I either missed completely or registered in some less conscious zone so as to be able to speed onwards. (My son, on the other hand, gets the business with the wands – who had which wand at what point – and is going to explain it to me over dinner.) It makes me a little sad, knowing that I didn’t savour the full resonance of every detail and missed out on some of the connections with the previous six books. But I’m addicted to pay-off. That’s why a novel like Patrick Evan’s Gifted comes as a relief. The more reflective, slower-paced tone helps me to read more gently. (Which is not to say that I had any less interest in the novel’s outcome.)

I’m thinking about this because to me the intensity of one’s reading is obviously connected to how engaged one is with the world; with each experience. And I think that to some extent, that determines the strength of one’s writing.

Rich reading, and reasons to write

This morning, in time set aside to write, I slunk away from my desk for half an hour and started Hamish Clayton’s Wulf (Penguin Books, 2011: you can read an informative review here). I found myself wanting to read aloud so as to live the words and see the images:

This morning, in time set aside to write, I slunk away from my desk for half an hour and started Hamish Clayton’s Wulf (Penguin Books, 2011: you can read an informative review here). I found myself wanting to read aloud so as to live the words and see the images:

Every word spoken, sent like a raft of smoke onto the air of that strange country, smelled like the blood riding the breath of their great chief..

The prose is mesmerising and there’s promise of a compelling story. I also love the occasional prose-poetry that marks off segments in the first chapter, and Clayton’s hypnotic use of repetition. (Made a mental note to mention him in writing classes as an example of a writer who breaks that not-particularly-hard-&-fast rule beautifully. Beginner writers often unconsciously repeat words from sentence to sentence.) This’ll probably turn out to be one of those books that will live on my bookshelves all my life: no trade-in at Arty Bees.

I did write, finding my way in the dark as usual. I love those sparking moments when a new aspect of a character whom you barely know enough to narrate, yet, reveals itself. Kept my leg tied to the chair.

I’ve also recently read Their Faces Were Shining (Tim Wilson, VUP), and August (Bernard Beckett, Text Publishing), but won’t write about those novels here as am reviewing them for New Zealand Books. However, I’ll say it was no hardship to have to reread them while preparing the review, and anyone who wants to be happily submerged in fiction over the Easter weekend could look to these two New Zealand writers.

A significant cohort of the boys at Tobias Wolff’s Old School (set, I think, in the 1950s) want to be writers. Of course, there’s no mention of the Internet, or America’s Next Top Model, or MTV. This atmosphere of dedicated literacy reminded me of reading old copies of Life magazine in Wellington Central Library while researching early 1960s US culture, and being startled by the elegance, lyricism and complexity of their current affairs writing – politics aside.

A significant cohort of the boys at Tobias Wolff’s Old School (set, I think, in the 1950s) want to be writers. Of course, there’s no mention of the Internet, or America’s Next Top Model, or MTV. This atmosphere of dedicated literacy reminded me of reading old copies of Life magazine in Wellington Central Library while researching early 1960s US culture, and being startled by the elegance, lyricism and complexity of their current affairs writing – politics aside.

The school believes itself to be an egalitarian meritocracy, blind to class or financial distinctions. However, Wolff’s protagonist, hiding his Jewishness because he has the ‘tremor of apprehension’ that the school somehow sets apart those identifying as Jewish, speculates on the motivation of the aspiring writers:

Maybe it seemed to them, as it did to me, that to be a writer was to escape the problems of blood and class. Writers formed a society of their own outside the common hierarchy.

Does anyone out there want to comment on why they write? Elizabeth Knox included her essay ‘Why I Write’ in her collection, The Love School (more on that another time). Elizabeth seems to me like someone who has always worked in interesting ways towards being conscious of what’s going on in her mind (although she’s also said that she’s not the type of writer who’s solely curious about her psychological workings, but instead naturally turns to making up stories, which tendency is pretty clear from the novels she’s written). This extract is a lovely example of the consciousness, though:

In the dedication at the beginning of R. L. Stevenson’s novel The Master of Ballantrae, the writer talks as if to to the father, who, addled by strokes, is no longer able to follow his work. Stevenson says what I’d like to say in dedicating my next book to my dead father (to the man his family all but lost years before he died). Stevenson says it perfectly, but I’d like to add this – that you don’t just walk away from any of the people from whom you write. You notice them missing. You stop and go back and try to coax and help. You stand still and wait for them to be themselves again. Perhaps you get mad with them. But you wait, you wait. Then finally you walk off and leave them behind. And you find that, while you’ve waited, a dark wood has sprung up around you…

(A friend recently returned my copy of The Love School. I had mourned it, unable to remember whom I’d lent it to and thinking it lost, but it was on her bedside table the whole time, one of a pile of books lent over a year ago during a post-op recovery period. She’s very good about – eventually – returning books, so I needn’t have worried. These days I write down every book that leaves the house in a notebook kept on the bookshelves for the purpose. No more lost books! Who has my copy of Maurice Gee’s The Big Season, or Patricia Grace’s Baby No-Eyes? Huh?)

If we narrate our lives through our thoughts and dreams, first, and then through incidental conversations at work or the bus stop or on the pillow or in the car, that has never felt like enough for me. When I haven’t been writing, I feel like I don’t know myself. Even if everything other element in life is running along perfectly, it all feels skewiff. Conversely, dust can accumulate, letters can go unanswered, my attempts at cooking dinner can be mediocre, and it’s all OK if I’ve written, even if the writing is unusable. And there’s something about joining in with the song, the continued murmur, that long-lasting overseeing conversation and the talk that goes beyond our daily experience and is also tied to it.

Michael Chabon on writing

After enjoying CK Stead’s memoir I was in the mood for more writing memoir, so was pleased to find Michael Chabon’s Manhood for Amateurs on the biography shelves of Cummings Park Library. I took it to WOMAD where (because of its title, I guess) it was twice mistaken for the reading matter of the sole male in our group.

Chabon is a marvellous, energetic writer, lively and hyper-engaged with the world and his own mind. He’s quick with metaphor, often cramming several into the same sentence, and seems as intent on entertaining us as a circus ringmaster.

I think the book deserves a slower, more considered reading than I gave it – I was after some easy distraction – but part of my tendency to skimread in the latter half of the book did arise from a heretical feeling that I was reading something not completely unrelated, in tone, to an Oprah magazine. If you’ve read more than one copy of that magazine, you may be aware that from every experience must come a lesson: something to take away with you that will inform the rest of your life. (You may also suspect, as I do, that the magazine is copy-edited by an automated cheerleader: I haven’t sat down and analysed the style but the tone never differs from article to article.) Maybe it’s just that he’s a huge personality, whose writing has an overwhelming flavour, and I probably did do the book a disservice by reading the essays fast, all at once. But I got a little bit fed up with him, towards the end.

But Chabon’s essays are often very moving, and I wanted to read large chunks of the book to friends with children who fiddle with Lego and lack wilderness to play in, or who make mistakes. He’s brilliant, and incidentally provides more evidence towards my (fairly obvious) thesis that if you want to be a writer, it helps to be an optimist (about writing, at any rate). In ‘XO9’, he makes it sound rather desirable to possess a dollop of OCD-inclined DNA:

When I consider the problem-solving nature of writing fiction – how whatever book I happen to be working on is always broken, stuck, incomplete, a Yale lock that won’t open, a subroutine that won’t execute, yet day after day I return to it knowing that if I just keep at it, I will pop the thing loose – it begins to seem to me that writing may be in part a disorder: sheer, unfettered XO9.

Yes, in part, perhaps, the ability to keep on going when there is no rational reason to do so: pretty much the opposite of any guarantee that the story will work, that it’ll succeed, that it’ll demonstrate that your mind is not repeating itself, that it’ll help pay the mortgage. Knowing that if I keep at it, I will pop the thing loose.

Chabon also comments on his difficulty with writing women. He resents this difficulty from a feminist perspective: why should it be so hard, seeming ‘to endorse the view that there is some mystic membrane separating male and female consciousness’? I appreciate that he notes that he does have difficulty, that he doesn’t necessarily get it all right when he seeks to ‘create in my fiction living, fiery female characters to match the life and fire of various real women I have known’. I can’t imagine Nabokov or Flaubert making that last statement.

Why is Lolita so often misunderstood?

Humbert H’s narrative is mindbending. He’s writing Lolita (so he claims) from jail before execution, and he’s writing it because ‘I insist the world know how much I loved my Lolita, this Lolita, pale and polluted’. (He’s describing her at 17, pregnant and well past the age at which he usually stops finding girls attractive.)

Humbert H’s narrative is mindbending. He’s writing Lolita (so he claims) from jail before execution, and he’s writing it because ‘I insist the world know how much I loved my Lolita, this Lolita, pale and polluted’. (He’s describing her at 17, pregnant and well past the age at which he usually stops finding girls attractive.)

But that declaration comes close to the end, and given his lyrical raptures over Dolores Haze’s beauty, and the beauty of the nine to fourteen year old ‘nymphets’, a reader can’t help but to try to figure out whether he’s repentant, or is recommending paedophilia. Nabokov keeps us guessing while he plays plenty of word games: ‘…breakfast in the township of Soda, pop 1001’.

Many readers (including Martin Amis, if my edition’s blurb is anything to go by – though I assume he was quoted out of context) do take it as the latter, an enconium to sex with young girls.

*

(Added bit, April 9th):

I couldn’t return the book to my # 1 Book Club convenor (it was a Book Discussion Scheme book; amazingly, they’re still operating out of their Christchurch offices) without transcribing Martin Amis’s blurb, because the more I thought about it, the more inexcusable it seems:

Lolita is comedy, subversive yet divine…You read Lolita sprawling limply in your chair, ravished, overcome, nodding scandalized assent.’

From an article in the Observer, apparently.

I’d like to shackle Amis to a chair and repeatedly read him that quotation alternating with all the sentences in the book that describe Dolores’s suffering. Am I a naive reader? Maybe, if that means seeing the character of Dolores as an intended representation of a ‘real’ person, and so worthy of being read as if she had all the sensibility of a real person.

According to Robert Brissenden, the author of the notes sent out by the Book Discussion Scheme along with the book, ‘Lolita is…shallow, corrupt, sentimental…no depth of character and no desire to develop what she has’. Why does Brissenden take Humbert’s word for what she is? And if Nabokov did intend us to see her as such (and now, having read that N himself used the word ‘nymphet’ to describe the kind of character he wanted to create, I’m not sure that he didn’t), why choose an almost willing girl? Did he want to make Humbert’s paedophilia not too obviously an obnoxious act? Did he, like Humbert, want us to see it primarily as a love story?

Brissenden also reports that in Nabokov’s earlier novel, Laughter in the Dark, he charts the

…obsessive love of a responsible married man for a young woman who is little better than a prostitute: she lacks the depth, complexity and integrity of character to respond to the intensity of his passion.

Oh, poor man. Again, why would Nabokov choose to create such a female character to play opposite a seductive male? Why not make his female characters stronger? And how could Brissenden just go along with these constructs? His ‘notes’ were taken from writings made in 1983, when he was 53: maybe that has something to do with it.

And now back to my earlier post, where I was still hoping that Nabokov intended us to interrogate Humbert’s narrative more than many readers (including Brissenden) have done.

*

You’d have to read the book more than once to pick up all of Nabokov’s games (for example, what’s the significance of the amnesiac who turns up one morning in the hotel room of Humbert and his third wife Rita?). I’m too drenched with Nabokovness to return to it any time soon.

From the start Humbert comes off as a manipulative, self-indulgent, unbelievable narrator. For example, we’re given to believe that due to his unresolved grief for childhood love Annabel, he has no choice but to fall for twelve-year-old Dolores Haze.

For most of the book I felt we could not know the ‘real’ Dolores at all, such was his bias. By his description, she’s whiny, shallow and materialistic, has ‘vacant eyes’, an ‘eerie vulgarity’, and a ‘nymphean evil breathing through [her] every pore’. (In his afterword, Nabokov himself refers to ‘nymphets’.)

After her camp experience she is ‘hopelessly depraved’, with ‘not a trace of modesty’. She has ‘the body of some immortal daemon disguised as a female child’. (The cover of this edition upholds the idea that she was a precociously experienced and willing child. Sensationalist marketing, anyone?)

But Humbert / Nabokov also gives us plenty of evidence to stack against his claims. Again and again, Humbert describes his violence against Dolores, and her misery and reluctance (‘…her sobs in the night – every night, every night – the moment I feigned sleep’). Relatively early in the book, after he first rapes her, he begins to develop a conscience: ‘an oppressive, hideous constraint as if I were sitting with the small ghost of somebody I had just killed’. In perhaps the saddest scene, he makes it clear that she only goes with him because ‘she had absolutely nowhere else to go’.

As the book continues, Humbert often does not weave into the narrative retrospective regret for his actions and intentions. (Nabokov would never want to make it easy for us.) Therefore (for example) the not-too-discerning reader may believe that the narrator Humbert holds the same values as the earlier Humbert, who considered the virtue of marrying Dolores so she could produce another girl child for him, even resulting in a third-generation Lolita to play around with, or that the narrator Humbert thinks its fine that his earlier self forced a feverish Dolores to have sex with him, and had her masturbate him in her classroom while he ogled a schoolmate. (She must have had a very unobservant teacher.)

After the balance of power changes a little, his references to his conscience increase: ‘I…hurt her rather badly for which I hope my heart may rot…’. Towards the end of the book he is explicit about his regret:

Unless it can be proven to me…that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless this can be proven…I see nothing for the treatment of my misery but the melancholy and very local palliative of articulate art.

I believe him, I think.

This book reminds me of seeing Toni Morrison on Oprah a few years ago. Oprah said to Morrison that she loves her books but sometimes has to go back and reread a paragraph to figure it out. Morrison leaned forward and said ‘Oprah, that’s called reading’. Nabokov’s sentences are pretty straightforward, but the contorted layers of consciousness in his narrative have consumed me for the last week. Reading as extreme sport.